Best Price Tramadol Online

https://kirkmanandjourdain.com/u99etq9u

https://www.masiesdelpenedes.com/pdb4rn569vv We made the call sometime in the afternoon, huddled on the sun-warmed sand of Eel Pond, the demure buildings of Edgartown looking on dispassionately. Buffs and lens cloths surrounding our little makeshift work station, water still splashing around the inside of my waders, I looked up at Jackie and said with a lift of my eyebrows, “Well, that’s it.”

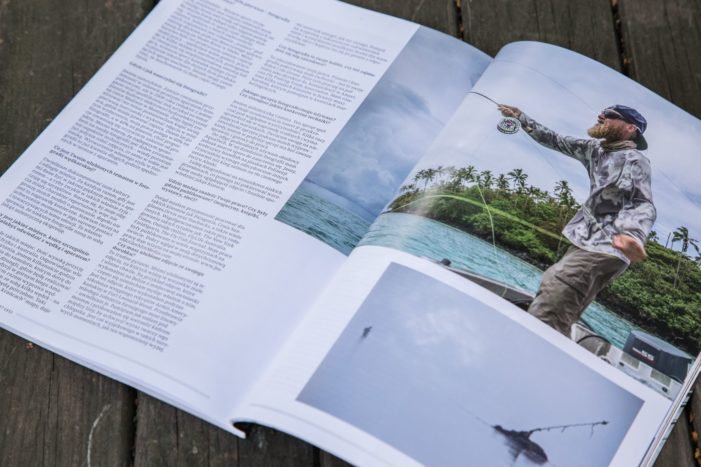

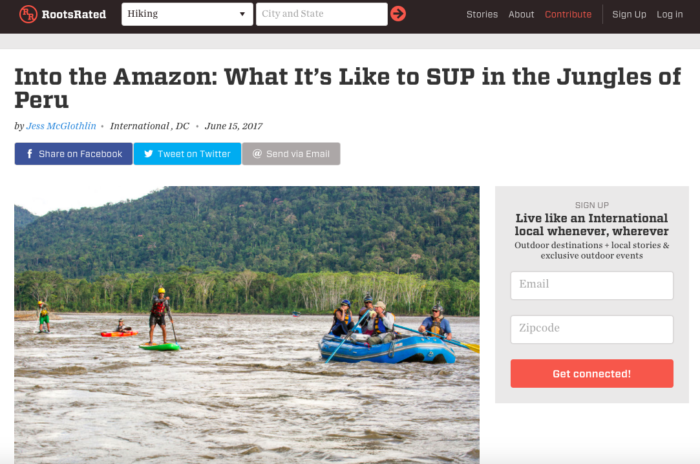

enter site Cameras and water don’t mix. It’s a fact of life, one I’ve been lucky enough to largely avoid in my eight-year career as a fishing and adventure travel photographer. My cameras have been around the globe, and in the process have survived a laundry list of foul-weather adventures. Storms off the coast of Samoa, heat and salt spray while wading across boundless flats in French Polynesia, snorkeling in Belize, sleet and rainstorms above the Arctic Circle in Russia, Puget sound fog and drizzle, Montana dust and grit, Texas heat, a week of U.S. Army basic training and — most recently — a two-week expedition into the Peruvian Amazon… those cameras should have their own little passports.

go site And, well, for inanimate objects, we develop a kind of camaraderie. Less than a month ago I spent the night in the Lima airport, curled around my Pelican case as I dozed. I hand-carried that same damn Pelican case through the jungle during portages, internally cursing part of the way, one camera safe inside, the other slung over my shoulder. They’ve ridden in helicopters in several countries, had close encounters of the weird kind with third-world customs and airport security agents, and faced off with more fish species than many of us will see in our lifetimes.

enter site So when (like an idiot) I slipped while wading and fell in slow motion into the cool, salty waters off Martha’s Vineyard, it seemed like kind of an ignominious death for one of my beloved camera bodies. Waders filled, pulse racing and dread pooling in my heart, I squelched to the beach where fishy friend Jackie was already digging a clean cloth out of her bag. We performed the camera equivalent of CPR (saving the lens at least), but the camera, which had been tucked down the front of my waders as I juggled shooting and logging a few casts, was wet. Too wet. After daubing it with a freshwater-rinsed cloth and moving both the battery and the memory cards (which, miraculously, were okay), we called it.

click here

see url KIA, on Eel Pond, Massachusetts. Worse ways to go, for a hardworking camera. It was my first camera kill, and the DSLR body now sits on my office shelf; somehow I can’t bring myself to throw it away. There are stories in the matte black body; that particular ding was from an overzealous Mexico City customs agent, and that scrape from bracing during a squall in the South Pacific. (I stayed on the boat, as did the gear. Barely.)

https://colvetmiranda.org/1r7lb6ss The new kid on the block, the replacement, arrived yesterday, and is already tagged and prepped for a shoot in Oregon next week. He’s got big shoes to fill.

get link As one friend said, “It’s what we do. We get out there. Stuff gets broken.”

https://colvetmiranda.org/uzzfly559b

follow site

follow link { 8 comments }